(MAY 10) — Can grave markers ‘talk’? Apparently, they can. And they say a lot.

Archaeologist Prof. Grace Barretto-Tesoro, PhD, of the Archaeological Studies Program (ASP) shared what stories grave markers tell as she discussed her study “What can we learn from grave markers?” at the conference via Zoom Of Crosses and ‘Culture.’

Her research found that identity of the deceased more than religion was emphasized on the grave markers.

“What can we learn from grave markers?” was part of a project Barretto-Tesoro started in 2008 and was presented during the conference’s first session The Bodies of Christ: Ethnographic and Archaeological Explorations of Faith in the Philippines.

Barretto-Tesoro’s research focused on grave markers in churches so the interest on religion was touched on.

“If there are references to religion, it’s mostly the motifs and the carvings on the grave markers, but I suspect these are driven by economy or are prepared by the lapida makers. Initial findings show that a lapida maker would obviously use the same motifs or use the same format for the several grave markers that they have prepared for different individuals across Southern Tagalog,” Barretto-Tesoro said.

“If there are references to religion, it’s mostly the motifs and the carvings on the grave markers, but I suspect these are driven by economy or are prepared by the lapida makers. Initial findings show that a lapida maker would obviously use the same motifs or use the same format for the several grave markers that they have prepared for different individuals across Southern Tagalog,” Barretto-Tesoro said.

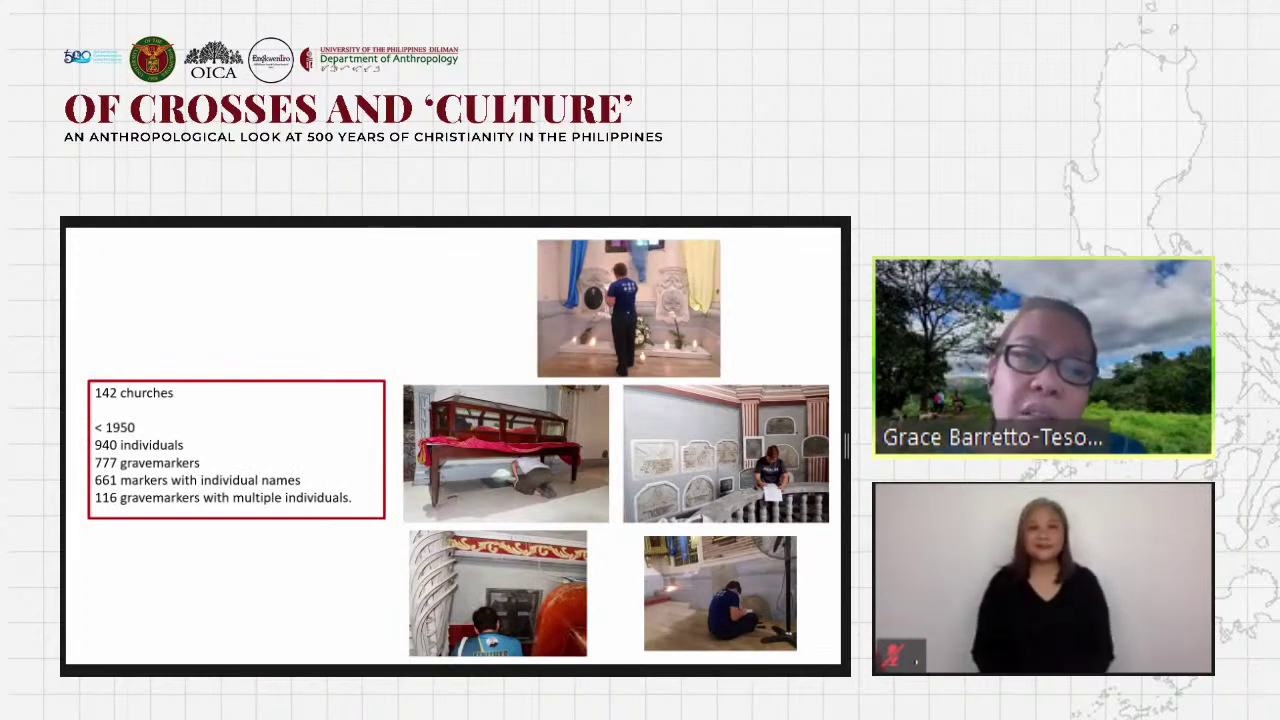

For the research she visited 142 churches in Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Quezon, Metro Manila and Bulacan, with the latter two being late additions, to look at grave markers.

Barretto-Tesoro further explained that the motifs of the grave markers were mostly for aesthetics and for status rather than belief in the religious or belief in the religion.

Her research covered the late Spanish period to early American occupation until the early parts of the Philippine Republic or the grave markers that were dated until 1950.

Ginhawa and identity were emphasized on the grave markers. Barretto-Tesoro explained in the Catholic faith there is that focus on the ginhawa or the well-being of the deceased and the well-being of the living family members.

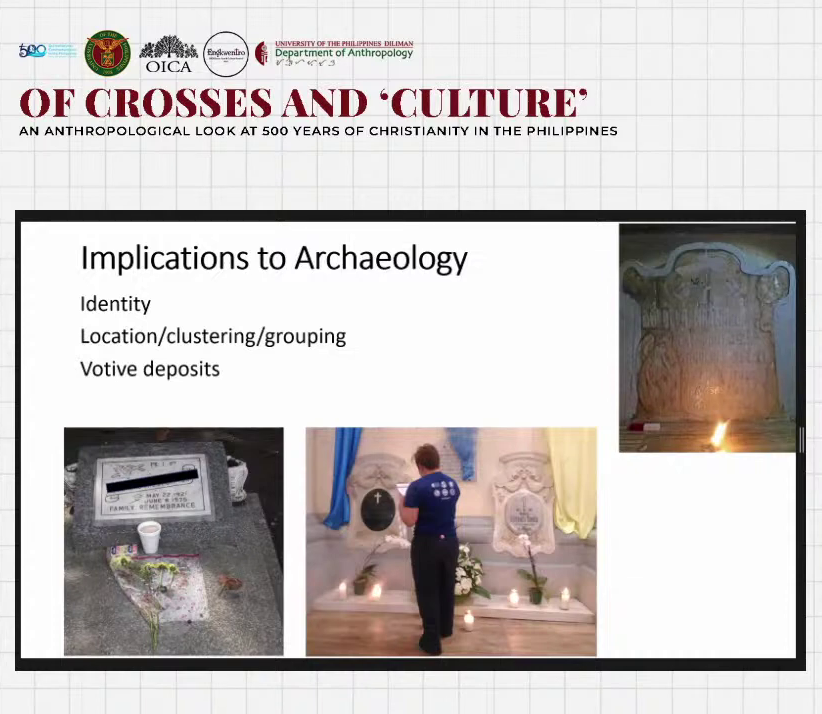

The archaeologist said she learned from the grave markers that there is a reciprocal relationship between the dead and the living.

“Apart from focusing on or highlighting identity on grave markers, it also highlights on the reciprocal relationship between the dead and the living. That the dead continues to protect the living and the living need to appease the spirits by continuing to offer and visit them even after several years after they die,” she said.

Most people buried inside churches were members of the society’s elite.

In addition, looking at gender and age differentiation, Barretto-Tesoro found that both male and female of different ages were buried inside the churches.

“The grave markers were mostly found along the walls or near the altar but many of the churches I visited no longer contain the bones due to church renovations so the tendency was to bury the bones in a common crypt under the church and if there was clustering of a common crypt they tend to belong to the same family,” she said.

In this research, Barretto-Tesoro was able to record 940 individuals and 777 grave markers. Of the grave markers, 661 had individual names and the rest had multiple individual names. “I took pictures of the grave markers, I recorded the epitaphs, I recorded the motifs,” she explained.

Her research brought her to see some uncommon entries on the grave markers.

“What is interesting for me is when I recorded grave markers that also included the time of death, either the exact time or indicated which part of the day: in the morning, at dawn or at night, and other information about the deceased. These would include the social status or the occupation, even the ethnicity of the dead,” she said.

There was also an instance that she was able to study a grave marker inside the Malabon church which had an epitaph engraved with “Tinawag sa sinapupunan ni Bathala,” or Summoned back to the womb of Bathala.”

“Bathala is the god of the Tagalogs during the Pre-Spanish 16th century period. That was interesting because it was allowed to be included for the grave markers inside the church,” Barretto-Tesoro explained.

Other grave markers have references to the dead, “So you’d know their civil status, if they are single or married, if they are young or old. Although, some of the markers do not really indicate if the person is married or not but you can deduce from the epitaph or the inscriptions if the dead had children and spouse, you’d know that the person was married,” Barretto-Tesoro said.

She also added that grave markers emphasized if the deceased were widows usually indicated by a Viuda or Vda. or Balo/Bao.

If the deceased was a minor the grave marker would emphasize based on what is written on the epitaph “because it is unexpected for children basically to have died before their parents.”

Barretto-Tesoro added there are other grave markers that have the profession or the public identity of the deceased.

“For public identity, I find it interesting that these are highlighted either they are parish priests or author of a book, either they are mestizo or not. What is common is if they are politicians. Even though they no longer hold the position at the time of death, they are still referred to as Mayor or Gobernadorcillo or Alcalde, and other positions such as medical doctor, teacher, professor, lawyer,” she said.

There was also a grave marker with a Gral (for General) written on it.

The research also delved on mortuary ideology, indigenous mortuary beliefs, and values and attitudes.

“I’m interested in the changing mortuary ideology from the pre-16th century to the Spanish occupation until the present. I would like to see how mortuary habituals change or how the transition occurred and if there are any, persistence in terms of practices,” Barreto-Tesoro said.

The conference last Mar.10 was an initiative of the UP Department of Anthropology in partnership with the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts and was part of “Engkwentro,” the UP Diliman Arts and Culture Festival 2021 held from February to April.