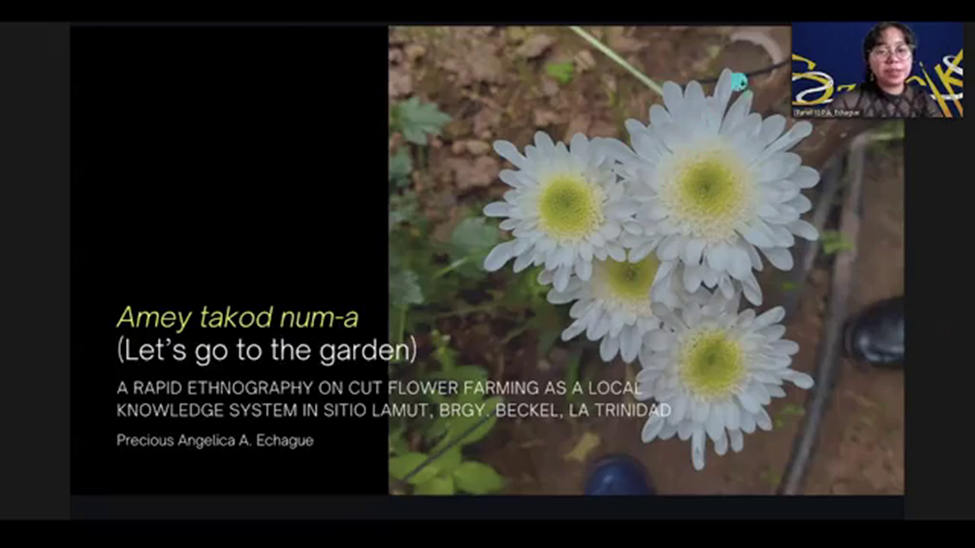

Amey Takod Num-A (Let’s Go to the Garden) by Precious Angelica A. Echague of the UP Diliman (UPD) College of Social Sciences and Philosophy tells the story of Kankanaey cut-flower farmers. It is also an examination of cut-flower farming in Sitio Lamut as a local knowledge system, providing livelihood and training to gardineros/locals.

Echague said the knowledge systems in her study are the different ways of knowing surrounding cut-flower farming.

“I also probed both shared and personal knowledge and how these information and practices are generated, shared, and negotiated,” she said.

Sitio Lamut is located in barangay Beckel in La Trinidad, Benguet. Most residents there engage in the cut-flower farming industry or gardening, as the locals refer to it. It is a floriculture business where farmers or gardineros plant flowers and then cut them from their stems to be sold and used for decorative purposes.

Echague shared that a 2016 study of the sitio found that some of the students who dropped out of school pursued cut-flower farming.

“And many of the cut-flower farmers or gardineros I met dropped out of school. One of them, who I will call Tita Maria, carried on to become a full-time gardinero after finishing elementary school to help their mother provide for the family and send her six younger siblings to school. So, many Filipino youth share the same story as Tita Maria, and in Barangay Beckel alone where Sitio Lamut is located, 19.63 percent of the 194 residents, ages seven to 21 are recorded to be out of school. And this does not include the number of high school graduates who were not able to continue their education to the tertiary level and other adults who also stopped schooling,” Echague said.

The youth of Sitio Lamut are usually taught by their parents to farm, albeit an alternative path to formal education, as their primary source of livelihood in the community.

Although Echague admitted that her study of the Sitio Lamut gardineros and cut-flower farming is limited and does not reflect the entirety of the experiences and processes of the cut-flower industry in the sitio, it nonetheless provided an insight into another learning pathway present in the sitio.

Echague said most of the gardineros she interviewed were not able to graduate from high school or college because of various reasons such as financial constraints, lack of motivation, and early marriage. Nevertheless, formal education remains to be important in Sitio Lamut. To further their children’s education and to provide for their family’s needs, they went on to become gardineros and work in the cut-flower farming industry.

“According to one gardinero that I talked to, sabi niya gardening is a blessing because despite not finishing his degree, he is able to make a living by cultivating flowers. And interestingly, even those who were able to finish college still work in the flower farming industry, and others even leave their jobs because of how profitable the industry is. To illustrate, one gardinero told me that a small green house can plant up to 20,000 semilya and harvest around 1,600 dozens of flowers and earn about P100,000 to P400,000 within three months and that is also depending on the price of the flowers at the time [because the demand for cut-flowers] is seasonal,” she said.

Echague explained that in an interview with Tita Maria, she told her that a person earning P25,000 or even P50,000 is better off gardening flowers for a living.

“It is important to note [however] that she is speaking from a perspective of someone who owns multiple green houses. So, in addition to that, I was able to meet other gardineros who graduated from college and did not pursue a job related to their program but instead went on to work in the cut flower farming industry, like Atty. Reyes. He was a teacher who did cut-flower farming or gardening. Sabi niya, hindi raw sapat ang sweldo sa pagtuturo lang. And now despite being a full time lawyer, he still works at the garden and supplies gardineros, because according to him there is still opportunity in cut-flower farming,” Echague said.

Echague found that in studying the cut-flower industry of Sitio Lamut, “One’s idea of orthodox education, where an approved body of knowledge is instilled into the minds of learners, is not applicable to cut-flower farming as a knowledge system.”

“Gardineros are instead exposed to the world where they continue to learn and to respond and co-respond to other beings present, whether human or other than human. Even an experienced gardinero who is supposed to have mastered gardening is constantly taught by the world. Despite the uncertain nature of gardening, it provides a sense of financial security to the gardineros of Sitio Lamut. It brings food to their table and sends their children to school. For others, it allows them to build three to four-story houses, purchase multiple vehicles, and throw high-grade kanyaw or parties,” Echague explained.

In addition, Echague learned that gardening or cut-flower farming is like gambling.

“Before going to this study, I wanted to prove that cut-flower farming as a knowledge system is a safe alternative to formal education and can provide a stable livelihood to the gardineros of Sitio Lamut. However, I learned that gardening is also gambling. Even if gardineros take calculated risks, [with] the emerging effects of climate change, the precarity of the prices of both inputs and produce, and the threat of losing their land, gardineros may be left with nothing,” she said.

Echague recommended that measures must be put in place to make cut-flower farming as a stable source of income for gardineros.

“For instance, on the issue of land ownership, laws regarding indigenous rights on ancestral lands and the protection of the environment must be revisited, and [gardineros] can be provided an avenue for asserting their right to self-determination,” she said.

Echague’s presentation was part of the first panel of the UPD Arts and Culture Festival 2023 (ACF 2023) online colloquium, Kaloob Saliksik: Bahaginan ng mga Artista-Iskolar ng UPD.

The online colloquium last March 8 was organized by the UPD Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts (OICA) and which aimed to be an avenue for the UPD artists-scholars to present their research works on the arts, society, and humanity.

Echague is a graduating anthropology major and is a scholar of the UPD Visual Arts and Cultural Studies Scholarship Program (VACSSP) under OICA.

According to the OICA website, the VACSSP is “in the form of a tuition waiver, (including waiver of other fees) or a stipend awarded by the UPD Chancellor through OICA to deserving UPD undergraduate students in the visual arts and in programs related to arts and cultural criticism.” The ACF 2023, held from February to March, had the theme, Kaloob Mula at Tungo sa Bayan: Artista-Iskolar-Manlilikha.

_____________________________________________________