Earliest pieces of evidence of basket and tie manufacturing on stone tools were recently found in Tabon Cave in Palawan by researchers from UP Diliman (UPD) and the National Museum.

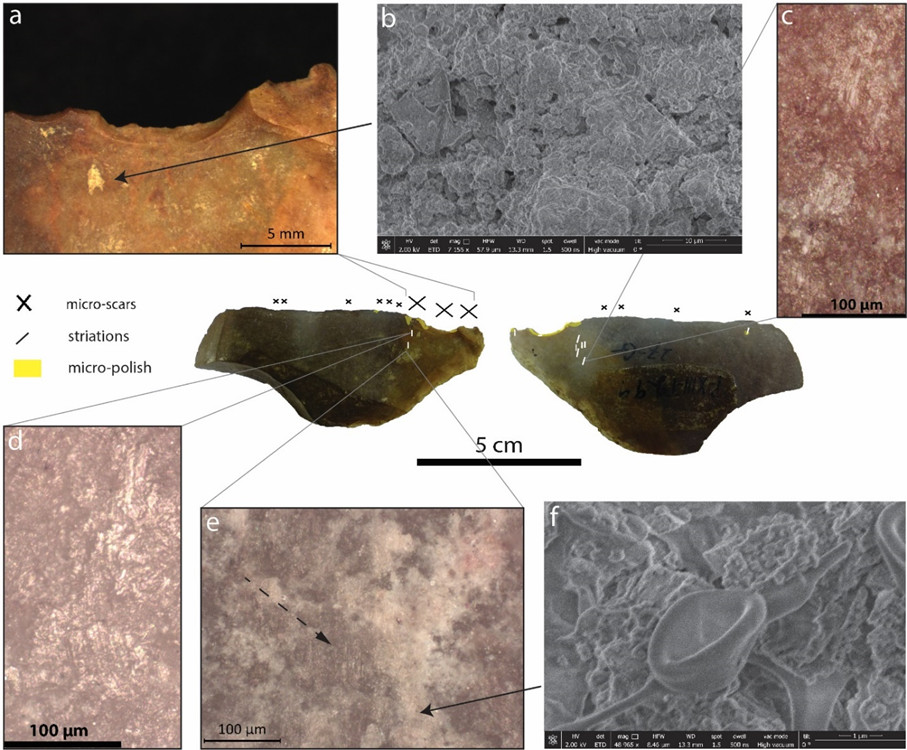

In the paper The Invisible Plant Technology of Prehistoric Southeast Asia, the researchers reported “the discovery of a use-wear pattern characteristic of thinning plant fibers on the three stone tools from Late Pleistocene deposits at Tabon Cave, Palawan.”

The pieces of evidence found date back to 39,000 to 33,000 years ago, determined through cutting-edge microscopic analyses.

“Fiber technology is extremely important. It allows making not only baskets and traps but also ropes that can be used to build houses, sail boats, hunt with bows, and make composite objects,” Hermine Xhauflair, PhD said.

In correspondences with UPDate Online, Xhauflair said the finding shows “that people in Tabon Cave were already processing plant fibers to make baskets and ties 39,000 to 33,000 years ago.”

The researchers claimed that their findings show that fiber technology was an integral part of late Pleistocene skillset.

“As early as 39,000-33,000 years ago, the Late Pleistocene inhabitants of Palawan possessed an elaborate organic technology and were processing plant fibers to make cordage, baskets, traps, or other composite objects,” the researchers reported.

They also explained that these botanical knowledge and technological know-how are still alive all over Southeast Asia (SEA) today and allow many communities to produce sustainable objects for their daily needs.

Xhauflair is an associate professor at the UPD School of Archaeology (SA) and head of the school’s Lithics Lab. She co-authored the research with Sheldon Jago-on, James Vitales, Dante Manipon, Noel Amano, John Rey Callado, Danilo Tandang, Celine Kerfant, Omar Choa, and Alfred Pawlik.

According to them, their paper also provides “a new way to identify supple strips of fibers made of tropical plants in the archaeological record, an organic technology that is otherwise most of the time invisible.”

According to the researchers, the pieces of evidence found “were identified based on a comparison with the distribution of use traces on experimental flakes used to turn rigid plant segments into supple strips, reproducing as closely as possible a technique that we recorded in ethnographic contexts among Palawan communities, and that is widely distributed in the region nowadays.”

The researchers claimed “These results show that seemingly simple Southeast Asian artifacts are hiding testimonies of a behavioral complexity invisible to the naked eye.” They have revealed these through use-wear analysis.

Use-wear analysis, as described by the Texas Beyond History website accessed on July 11, takes into account “the fact that repeated actions performed with a stone tool leave microscopic and sometimes macroscopic evidence of friction. These wear patterns and striations differ slightly depending on the material (wood, dirt, plant, bone, and meat) and the action (chopping, cutting, and abrading);” and in this way “scientists are able to link a tool action.”

Xhauflair, the lead author of the research said the study “pushes back in time the antiquity of an important national handicraft in the Philippines.”

The researchers pointed out that their discovery “highlights both the technological skills and botanical knowledge possessed by the inhabitants of southern Palawan at the end of the Pleistocene.”

“Our results add to the recent evidence showing that a plant-based perishable technology indeed existed in the region during prehistory,” they said.

The Invisible Plant Technology of Prehistoric Southeast Asia is published in PLOS One, a peer-reviewed open access mega journal by the Public Library of Science. — With a report from the SA