Early Monday morning, we lined up for a swab test at the Molave dormitory in the Diliman campus of the University of the Philippines, less than two kilometers from my home. I decided to take a stroll there, eager to stretch my legs after five days in isolation.

The contact tracer had arranged for the appointment flawlessly, and we were done in no time; I didn’t have to open a book to kill time. We signed up, we blew our nose, we sat before a booth encased in acrylic glass from which a health worker in full space suit-like PPE stretched out his arm through a hole to swab our nostrils for samples.

It wasn’t as bad as I thought; discomfort was brief. It was my first time to get the RT-PCR test for Covid-19; the few others with me had done it before, rather frequently in fact, because of the university’s aggressive testing policy for employees who were usually at risk at their work. The staff at the Molave testing site were from the Health Service, the infirmary which in our school days long ago we called infirmatay, a joke connoting its lackadaisical staff.

But the campus has transformed in this time of the pandemic, taking an energetic response to the needs of a health crisis. The Molave dormitory is not only a testing site, it also serves as an isolation center. There is another site, in the women’s Kamia dormitory on the other side of the campus. The hostel of an institute for education development was turned into a lodging house for front-liners working in nearby hospitals. And the campus pride is the Philippine Genome Center, which has become one of the country’s laboratories for testing the virus.

Exactly two weeks before my swab test, I had my first jab of the Sinovac vaccine at the campus gymnasium, again one of those buildings we retreated from in our university years. Today it’s a sports center the size of three basketball courts. The gym is home to the College of Human Kinetics, the current site of a vaccination center that is probably the biggest in Quezon City where the campus is located – I overheard the mayor saying that when she visited on the day of a dry-run for the volunteers.

The country’s vaccination campaign began on the first of March, opening up centers – schools or malls – first in the capital’s 16 satellite cities. The vaccines, either Sinovac or Astra-Zeneca, arrived in a burst, and then petered out until a next shipment came. The pace was unbearably slow and limited only to front-liners working in hospitals, senior citizens, and those who had comorbidities.

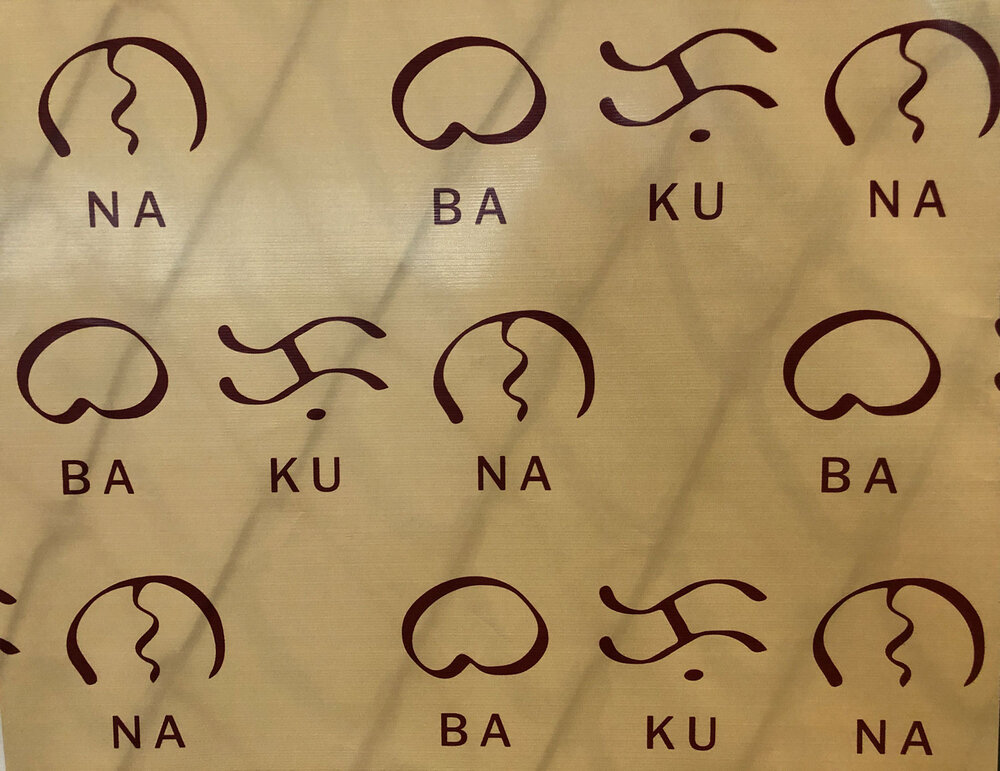

On campus, the gym’s vaccination center – Bakunahan sa Diliman – had only 100 doses or so a day, and after a week in operation in late April it had to stop temporarily because city hall, which supplied the shots in a quid pro quo arrangement with the university, had ran out of Sinovac. A next batch is expected to come soon, perhaps including Russia’s Sputnik vaccine, which was rolled out in another city.

The gym was spacious enough to have more people coming each day, if only we could shorten what experts say would take until late 2022 or longer to reach herd immunity. We’ve reached slightly more than one percent so far of vaccination in a population of 110 million.

While city officials told the university not to worry about vaccine supply, UP was asked to provide the rest: the venue (hence, the gym), used borrowed refrigerators and standby generator sets pulled in from donors and different buildings around the campus. Most important were the volunteers – from physicians to vaccinators, who could be nurses, veterinarians, physical therapists, dentists, or medical students, to health protocol enforcers, data encoders, web designers, food brigades, and perimeter security.

———-

The “vaccinees” often came early, when the line was short, and they were done in less than an hour of going through an orderly maze of orientation, screening, and finally, the vaccination itself. The floor plan was done by Lizza, a faculty member teaching interior design, and another professor from industrial engineering to make the sequence of steps flow.

Monina, a lady marshal who used to be an airline attendant, in true form ushered people as if they were getting ready for a flight: everything was set up; the papers were filled and registered; an animation video guided those who might feel worried or uncertain, because conspiracy theories have flooded social media. Sinag, who used to chair the mountaineers club, who grew up on campus, was the energetic host welcoming older professors by name as they strode into the vaccination site. They even got a free pack of biscuits when they were done getting the jab.

The doctor who gave me my jab, injecting me almost crudely with a slim syringe on my upper left arm, was a 23-year-old medical student. Vince, his name, was stamped on my vaccination card indicating 28 more days to go before I got the second and last one. He will be graduating this year from the College of Medicine. This, he said, was supposed to be part of his internship because, as things were going, they couldn’t even go out to the communities to treat people face-to-face.

If an outsider were eavesdropping on our conversation, we could have been red-tagged for expressing our disillusionment with how the government has been handling the health crisis from the very start. It couldn’t get itself out of priorities intensely driven by politics, leaving mainly the people to fend for themselves and to rely on their local mayors. As the young doctor saw it, people became so vulnerable to misinformation concerning the coronavirus.

He had seen the husband of a close friend die of Covid-19; it was as real as it could get. As an intern, he could only do so much in conducting tele-medicine. Politics and the slow burn of hopelessness amid the crisis reinforced his desire to jump ship – this wasn’t the kind of country you’d like your children to grow up in, he said, but there was the duty to serve, an obligation to practice for at least three years for being a scholar of the state university’s prestigious medical school. Besides, he couldn’t “back out from being a doctor.” It was his chosen profession.

We talked through our face masks, and our face shields. The shields were more of a hindrance to breathing and seeing, and we both agreed in our own conspiratorial voices that perhaps a politician or businessman close to power was financially profiting from the order for people to wear an added barrier of clear plastic, a rule not imposed in other countries. One can’t walk into a supermarket or any shops without a full-face shield, the goggles type would not do even if they protect the upper part of the face. Have we become cynical? We laughed.

I thought of the long chat I had with the doctor at the Philippine Genome Center, whose building, rather inconspicuous, sits at the science complex off the legendary academic oval on campus. I could have sat all day listening to Dr. Marc Edsel Ayes, 34 years old, so young, so bright, someone who could distill scientific processes into simple analogies. “It would be nice if we have a Fauci-like figure,” he said, referring to America’s chief medical advisor Anthony Fauci – the man who explains to the world what the virus is all about.

Fauci was Ayes’ god when he was studying internal medicine. The medical journal he read in school, of which Fauci was the editor, was like his bible. Ayes found himself at the genome center as a protégé of one of the center’s leading doctors, doing genetic sequencing that was mostly centered on agriculture and aquaculture. He was keen on burying his nose into cancer cell research, until the pandemic struck, and he immediately shifted gears with his mentor who helped invent a local COVID-19 test kit early on, in an effort to carry out mass testing, a task the government botched miserably, that and contact tracing.

In mid-December 2020, the presidential palace – where meetings are held by the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases, or IATF for short, a group of senior officials including the health secretary whom doctors and nurses had wanted dismissed from the job – reached out and asked the genome center to go beyond RT-PCR testing so it could undertake surveillance of a slippery enemy whose mutants were re-emerging suddenly on a global scale. By end-February, the center discovered a unique Philippine variant, called the P3, taken from a swab somewhere in the western Visayas. The variant had a mutation similar to the Brazilian one.

Though we had to be seated al fresco by the center’s entrance steps in monobloc chairs within safe distance of each other (the center is highly sanitized and off-limits to visitors), there was awe and fascination as to what it could do in the field of science. I understood that we hadn’t been moving as fast as we should, and that Ayes thought there should be a “bridge between bench and bedside,” between scientists and medical doctors who could meld their studies and research into cutting-edge discoveries and protocols. As far as he could tell, we were behind.

The center, however, moving ahead in its research, had been housing about 1,000 tera-bytes of information in one of the most expensive machines (costing nearly 200 million pesos) that could read a collection of DNA (the cookbook) and RNA (the recipes) in proteins (the actual dish). That was too much information to untangle in one afternoon.

I was just fascinated listening to him talk outside my realm of reporting, he who was conscious of his American accent: he was born in California and raised in Hong Kong and Singapore before his family returned to Manila. I was amused that he was wearing a UP Fighting Maroons tee-shirt, though he was a graduate of the Ateneo medical school and took his master’s in molecular science at the University of Bristol in the UK.

Isn’t this why we love UP? For the exchange of ideas, nosebleed, quirky, intense, left-leaning or otherwise, also red-tagged by the defense department early this year, which accused the university of being a communist breeding ground. It was all too much, when the campus had to close down and students had to resort to online classes in this health crisis. Chancellor Fidel Nemenzo organized a task force to mobilize personnel and resources to help keep the pandemic at bay. The undertaking was so huge it didn’t stop one professor from writing Nemenzo to express a conspiracy theory that the vaccination against COVID-19 was a genetic experiment.

In normal times Nemenzo would have pursued a dream of seeing UP become a smart campus, one with environmental sustainability – it is the only patch of green accessible to the public – and a commitment to biodiversity. The campus is where one could find various species of birds, like the orioles that darted from one tree to another while I listened to Dr. Ayes, the owl beside the Kamia dormitory, the nightjar by the museum. “UP produced free thinkers and innovators, hindi lang ito para sa mga leftists (it’s not just for leftists),” said Nemenzo.

———-

I was one of about 700 who filled out the vaccine site volunteer form in the first three days that it was uploaded. By now there are almost 1,000. A first batch of 500 would take turns over a period of 12 weeks and, after hours of Zoom meetings, we were called in for a simulation. I had joined because it was an opportunity for me to leave the house and walk in the campus, which shut down when the highest level of lockdown was enforced once again between late March and early April.

Taking on the small task of being a marshal, guiding people in, preparing their documents, I came across one of the volunteers, an assistant professor teaching anatomy and exercise physiology at the gym. Getting myself into yet another long conversation, this professor, Revin Santos, who was of the same age as Dr. Ayes, took his master’s in Australia and summarized the gist of trying to survive in the pandemic. It is the paradox of moving, exercising, shaking our bones, muscles, using energy, in a quarantine where we are trapped at home. It might also be the key to not succumbing to any possible mental health problems.

He loves cycling. His first name reminds me of a town in France through which, I told him, a bike path stretched 90 kilometers. On campus, biking is no longer allowed on the oval, which is about two kilometers, even before the pandemic; bikers now have to skirt the outlying streets except in places near the isolation centers. He offered to fix my bicycle’s gears so I could move around more, instead of just walking. Volunteering at the gym was an exercise as well, walking from here to there, the ventilation clear and cool in a structure that resembled a Quonset hut.

“If an outsider were eavesdropping on our conversation, we could have been red-tagged for expressing our disillusionment with how the government has been handling the health crisis from the very start.”

How could it be that more than a week later I would get a call from a contact tracer who said I had been exposed to a university official who tested positive? When did it happen? At a lunch break in the office of a professor whom I ran into after he had finished his vaccination; he had invited me and two others to his office nearby.

He had books everywhere. His windows were open. He had a giant television screen showing real time street life in Tokyo, and didn’t we wish we were there? He boasted of Kalinga coffee freshly brewed in a pot. He ordered lunch at Salad Stop, the wraps easy to eat. We sat away from each other at a table that was once used by 11 members of the university’s Board of Regents.

None of us had any symptoms. Since the series of quarantines began in March last year, I have had few chances of getting infected, leaving my place about once a week for “essentials” – now a byword — and doing my regular walks around a long driveway (if not on campus when it was open during the holidays). Dr. Ayes said that if you didn’t have to be in house confinement, it was better to be outside than inside.

It was odd to “isolate” (a term made redundant in our circumstances) myself as the contact tracer told me. How much more isolated could I be, living alone in my condominium? The day came when I had to be swabbed for the first time. There was nothing much else to do. On that early morning, I relished the walk to the campus after some days of being cooped up.

The following day, there was news from the contact tracer who texted: “Happy day po, the result of your swab test is negative.” I also received the comprehensive test result by email from the genome center no less, signed off by the laboratory manager. Who else but Dr. Ayes.

article from: http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/getting-swabbed-and-jabbed-for-dear-life