“The archaeology of the colonial landscape is very central to the trajectory of Philippine history and culture today,” said Prof. Victor J. Paz, PhD in his keynote lecture at the online conference, “Indigenous Responses to Colonial Incursions,” of the UP Archaeological Studies Program (ASP).

In the second part of his lecture, entitled, “An Archaeology of the Native Response to Colonial Incursions,” Paz focused on the effect of the creation of the pueblos after the conversions of the Filipinos into Christianity and their communities into pueblos, the implementation of the reduccion, and the eventual creation of the plaza complex.

Paz described his lecture as an attempt to present archaeology, and its use is “metaphoric and symbolic in giving value to our study of the human past, of our ancestral culture, and our immediate culture.”

Total change. The effect of pueblos and the plaza complex totally transformed the way communities settled in the landscape, so much so that the settlement patterns were totally transformed, the former ASP director said.

“From hence, since the creation of pueblos, people were gathered around, rather than scattered; rather than following the banks of a river or of a stream or scattered in the landscapes in the hills, most people were gathered into pueblos. In the middle of the pueblo that is formally created, you have a plaza. From that point on, you then will have a reinforcement of the idea of a pan-authority, like a large datu over everyone else in this concept of a king or a queen that is well away in this imagined place called the Iberian Peninsula,” Paz said.

Shift in power. According to him, the persistent pattern also shifted the authority from the founding families that created the settlements or the “founder cultures — the entire phenomena that we still see up to today” to a new set of people, the officials appointed by the Spanish government.

The change had a massive impact on the consciousness of the people and created “this idea of commonality too, across landscapes, across islands that wasn’t present prior to the creation of all of these social engineering manifestations.”

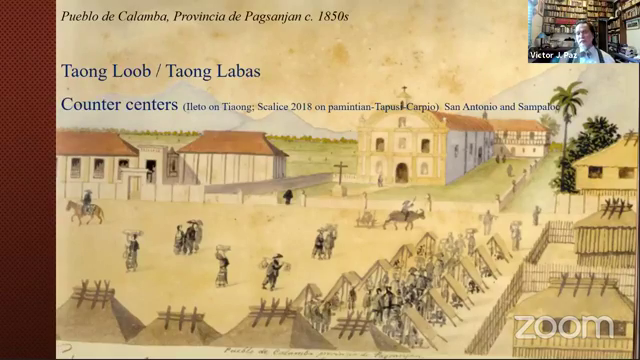

Taong labas, taong loob. The change however, was not that simple, according to Paz.

“We will see at the get-go, there were people who refused to be just placed inside the pueblo,” who were referred to as “taong labas,” he said.

Paz further explained that “taong labas” is also the “taong loob” who gets out of the pueblo when a crisis occurs in the “loob.”

The crisis could be as simple as not being able to pay the cedula, or a complex one like an outbreak of cholera or a threat of an attack by slave traders, can be reasons why “the people tend to get out of the pueblo,” Paz said.

He explained that when there was a threat to the pueblo, people opted to leave and not live inside the pueblo. And this phenomenon repeats itself.

Counter center. Paz said a furtherance of the taong labas is when a cluster of such people chooses to live together and creates a “counter center.”

An example are the people of Tapusi, which Paz said was a place for people who were escaping or did not like the way pueblos were run.

Tapusi became known enough to enter the folklore of the Southern Tagalog people and were described as “those people living around Laguna Lake … the legendary place where it is a settlement that by all descriptions running like a commune.”

Paz said thatin some cases when a counter center attains a certain level of success, the central government “will appropriate it by sending a priest or by acknowledging it as a new pueblo giving it a new name, making it a San or Santa or whatever, and then giving it a church.”

In Laguna, the place San Antonio (in San Pedro) is a classic case.

“San Antonio was a counter center, and Antonio was the founder. As the folklore goes, they just put a “San” and since its beginnings, it has been the center of the so-called banditry, social movements, the Katipunan revolt, Papa Isio settled there, made a base at the outskirts of San Antonio. Ka Elias went there when he was being hunted before he surrendered, Asedillo came from there — another social bandit in 1935, HUKBALAHAP (Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon), the NPAs (New People’s Army) up to today, consider that area as like a liberated area and very sympathetic to their movement. And just across in Quezon is Sampaloc. Sampaloc has the same history,” Paz said.

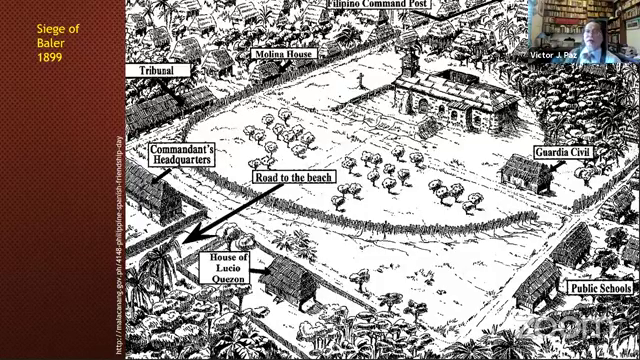

A good demonstration of the multilayered effect of the change of landscape was during the 1899 siege of Baler in Aurora. Paz explained that Baler in the late 19th century was so rustic and still very provincial and yet it had the “plaza complex concept being introduced or being lived in.”

On July 1, 1898, 50 Spanish soldiers laid siege to and fortified the town church in Baler, Aurora, fighting off the Filipino revolutionaries. By December 1898, Spain had surrendered claims to the Philippines and ceded to the Americans with the Treaty of Paris. Unaware of this event, the Spanish troops in Baler continued to fight and barricaded the church for 11 months. On June 2,1899, the Spaniards, now only numbering about 30, finally surrendered to the Filipinos.

“You have the church in the middle, and then you have the siege, and then you have the eventual negotiation that allowed for the Spanish soldiers to surrender peacefully and survive this siege. What I like about this is it doesn’t matter how big or small the settlement is, the effect of the pueblo as a settlement bank with a plaza or some sort in the middle has now become the baseline in creating settlements which has an effect in the way people think about their role and their engagement in the landscape,” Paz said.

Lasting impact. Paz summarized that, “the colonial experience under Spain is just one of several periods in Philippine history that had a lasting impact on our culture. Adoption and adaptation, and integration were inevitable. The colonial experience was not total but substantial enough to change the settlement patterns, the cosmology and its iconography, our polities, and for better or for worse, it has dictated the trajectory of our history.”

Paz is one of the country’s senior archaeologists and is a faculty at the ASP. He specializes in archaeo-botany, Pacific archaeology, and Southeast Asian archaeology. His research throughout the Philippines include Palawan, Agusan, Quezon, and Batanes. The two-day online conference (Aug. 23-24, 2021) was in celebration of ASP’s 26th anniversary, and part of ASP joining the nation’s Quincentennial Commemorations in the Philippines (1521-2021).