Books in the Philippines generally tend to have short shelf lives. Our environment is host to many conditions that are not friendly to books, conditions that constantly threaten their survival. One of such is the frequency of fires.

As a book historian, I know this all too well, for there is no dearth of accounts of the burning of books throughout Philippine history. Take, for example, the fires at the San Agustin convent in Intramuros in 1574, then in 1583, and yet again in 1586, each one razing the structure to the ground and consuming all the possessions of the poor Augustinian friars, including their books. By the time of the 1586 fire, they had built up what has been described as a “very rich library,” one of the best in Manila at the time. But it was just as vulnerable as any other library, best or worst, to the ravaging force of fire.

Another important collection lost to fires is the manuscripts of Francisco Baltazar (Balagtas), which was left with his family after his death in 1862. While Balagtas is generally known primarily for Florante at Laura, he actually wrote many other poems and more than a hundred plays. Only a fraction of these works has come down to us today because of two fires that hit Orion (now Udyong), Bataan where his family lived.

Then there was the fire at Plaza Moriones in Tondo in 1940. It was actually a bonfire, the centrepiece of a protest action by a group of writers who were of the younger generation of Tagalog authors. Decrying the stagnant state of Philippine literature and blaming commercialism as the impediment to progress, they cast into the fire printed novels, short stories, poems and other writings that they considered unworthy of being passed on to future generations. Most of the works they burned were by the older generation of writers.

These fiery incidents and the many more like them serve well as data in my work as a book historian, but their aftermath—the loss of books, documents and other texts—are the stumbling blocks and the dead-ends of my research, which have caused me much frustration. The feeling seems petty now. I knew all too well that books have been lost to fires throughout Philippine history. But, as we in academe perhaps sometimes forget or fail to acknowledge or don’t realise, knowing something—reading, writing, speaking about it—is one thing; experiencing it yourself—seeing, hearing, smelling, feeling it—is quite another thing altogether.

On 1 April 2016, a fire razed the Bulwagang Rizal, better known as the Faculty Center (FC), in the Diliman campus of the University of the Philippines. Built in the 1960s and site of the administration and faculty offices of the College of Arts and Letters (CAL) and the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy (CSSP), the FC was second home to hundreds of people who walked its halls everyday—faculty members, administrative and support staff and students. While some parts of the building were spared from the flames, the larger part of it, most of it, was totally gutted. The fire ate up everything in its path.

If this were just another book history case I was researching on, I imagine that, being keen on irony, I would’ve gotten a kick out of it. Consider this: a fire that happened in a place of high intellect on April Fools’ Day and on the day right after the end of Fire Prevention Month; when just the day before, a colleague concluded her lecture in class dramatically (as she usually does) with the line from Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, “I’ll burn my books…!”; when the burning of the building had long been a running joke among its occupants.. No one is laughing at the joke now. I myself am not so amused by the ironies now that I know not even a paper clip survived in my room.

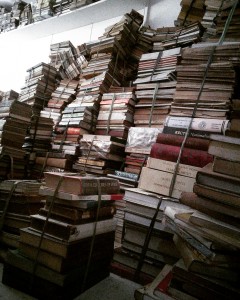

We of the FC are so grateful that no one was hurt in the fire, yet we are wracked by a deep and painful loss nevertheless, as if we ourselves were gutted. Our books and readings, data and records, research materials and writings, personal and professional mementoes, gadgets and equipment acquired, collected, and maintained carefully through the years, not without difficulty or sacrifice, as anyone familiar with the UP budget would know—all gone.

At the CAL meeting, held while FC was still burning, there were grim faces and teary eyes all around the room. It felt like a wake. While the fire victim in me was grieving, the book historian in me was fascinated to find that what my colleagues were mourning most for was the loss of books—the ultimate tools of our trade. For some, it was their entire libraries, books of a lifetime, housed in their FC rooms for decades or just set up a few months ago, as in the case of a young colleague who recently got tenure and, finally, a room of her own. For others, it was significant sections of their collections, transferred into their offices due to lack of space in their rented apartments. For most, it was their working libraries, the books they used for their teaching every class day, every semester, every schoolyear throughout their entire careers so far.

The Department of English and Comparative Literature (DECL) suffered a particularly gut-wrenching loss: In February this year, the family of the late Francisco Arcellana, National Artist for Literature, donated his library to the department. It comprised over a thousand books, the most special ones marked with annotations in his hand and inscribed by their authors for him, along with rare first editions of Philippine literary works. Some of my colleagues and I were in the process of sorting through the collection. It was tedious and literally dirty work, but it came with the privilege of catching a glimpse of the life of the mind of a brilliant man who was a pillar of Philippine arts and letters and who was once one of us, a member of the DECL faculty.

The best items of Arcellana’s library are irreplaceable indeed. Many of the books lost in the FC fire, though, are not. New copies may be acquired, be it in print or digital form. But this, I know, is cold comfort for my colleagues and me. There is, on the one hand, the practical issue of the cost and time entailed in replacing those books, which any UP teacher would be hard-pressed to address. On the other hand, and this is just as real an issue, there is the psychical and emotional value of those books. You may buy a new copy of a book lost in the fire, and it would have the same contents and serve the same purpose as your previous copy. But it would never ever be that particular book that has been with you since your BA, through your MA, up to your PhD days; or the one you bought during your first overseas conference and had signed by the author who was the keynote speaker; or the one your favourite professor, now deceased, bequeathed to you when she retired. Once a book has been owned, it is never the same copy as any of the hundreds or thousands of the same title. That’s what makes the printed book so special, the life that becomes attached to it and that it expands, the story it acquires beyond the story it tells. I don’t think that the digital book is quite able to transform itself and its reader this way.

In time, I am sure that we will get over the loss of our books; we will move on and carry on owning, reading, and writing other books. I am certain, too, that the memories of joyful learning that we all shared in FC and the friendships that we forged there, no fire can ever burn.

Bangon CAL-CSSP! Kaya natin ito!

=======

May Jurilla is Associate Professor at the DECL, where she teaches book history and literature. One of the books she lost in the FC fire was her hardbound copy of the classic Chaucer’s Poetry in Middle English, edited by A.C. Baugh, with her notes from graduate school and for the English 122 and 233 classes that she taught.

The original version of this essay appeared in Shorthand the UP English Department on Tumblr at http://updeclshorthand.tumblr.com/post/142242695044/this-one-is-for-the-books