“Journalists must advocate to end impunity.”

UP College of Mass Communication (CMC) Prof. Danilo A. Arao reiterated the call of Joel Simon, Executive Director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in his lecture “Making Sense of the Senseless” at the CMC Research Brownbag Series last Aug. 30 at the CMC Auditorium.

In his lecture, Arao discussed his ongoing doctoral dissertation which delves on how the culture of impunity affects journalism (or media practice in general) in the Philippines and vice versa. Arao is currently completing his doctoral studies in Journalism at the Technological University of Ilmenau, Germany.

According to his research supervisor Martin Löffeholz, a known global journalism studies scholar, “There is lack of in-depth research on the interaction between the culture of impunity and journalism thus my research could fill that gap,” Arao said.

“Philippines is an interesting case study because we are among the freest countries but we are also one of the countries which have the most number of journalist killings,” Arao added.

Arao said the figures from the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines show 174 journalist killings from 1986 to 2016. The year with the most number of journalists killed is 2009 where 32 journalists and 24 other persons were killed during the Ampatuan massacre in Maguindanao on Nov. 23.

The Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) of the Philippines reported 147 journalists were killed from 1986 to 2015. “The CMFR has a lower count because they try to ensure that the motive is identified,” Arao explained. Nonetheless, “the numbers are not far from each other and is still alarming.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) produced a report, the Global Impunity Index 2016, which placed Philippines in fourth behind Somalia, Iran and Syria. CPJ’s Impunity Index calculates the number of unsolved journalist murders from Sept. 1, 2006 to Aug. 31, 2016 as a percentage of each country’s population. Simon is the executive director of CPJ, a New York-based independent organization.

In 2015, the International Federation of Journalists reported 146 media killings in the Philippines from 1990 to 2015, placing the country in second place to Iraq which have 309 media killings in the same period.

The culture of impunity thrives because of the “impossibility of bringing the perpetrators of violations to account for they are not subject to any inquiry that might lead to their being accused, arrested and if found guilty, sentenced to appropriate penalties,” according to the Equipo Nizkor and Derechos Human Rights of Latin America.

As the culture of impunity thrives, which comes in the form of media killings, harassments and intimidation, it results into “acquiescence and chilling effect. This makes the society, even the journalists, comply with anything because of fear.

This could only be countered through a culture of resistance.

Arao cited Stephen D. Reese who said that journalists “are not limited to being the disseminators and interpreters of news, but above that, their major role is to be adversarial in delivering it as well.”

Similarly, Simon added that “Journalists must actively defend the rights of all people to gather news, express their opinion, and disseminate information to the public. It’s just not simply to report.”

This culture of impunity needs to be addressed before it embeds in the national psyche and becomes normalized in the society making impunity a new standard.

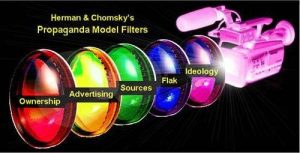

Arao used the Hierarchy of Influences Model (HIM) of Reese and Pamela J. Shoemaker and the Propaganda Model (PM) by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in discussing how the culture of impunity can affect journalism, and how journalists, through the culture of resistance, can put an end to impunity.

The HIM describes the five levels of influences, from the individual to the ideological or societal level, which indirectly influence and shape media content. These levels affect the “level of analysis on what news to produce and how to produce it. The levels can also work separately or in conjunction with one another,” Arao said.

The PM, on the other hand, discusses the five filters which screen what news will be made available to the public. These filters–ownership, advertising, news sourcing, flak (disciplining of journalists) and external enemy or threat–determine what events are deemed newsworthy, how they are covered, where they are placed within the media and how much coverage they receive. It focuses on the “inequality of wealth and power and its multilevel effects on mass-media interests and choices,” Arao explained.

In closing, Arao reiterated that journalists, along with the rest of society, must be empowered to go against the culture of impunity. He is an associate professor in the Department of Journalism in UP College of Mass Communication.

The brownbag series, which started in 2004, is organized by the UP CMC Office of Research and Publication to provide a venue for faculty members to present their research outputs. (With reports from Raymund Creencia, Trisa de Ocampo, Hanzvic Dellomas and Jo-ev Guevarra.)