After typhoon Yolanda in 2009, the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 and the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, people became more conscious of the need for disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM). Recognizing how destructive natural phenomena can be, 10 academic units at UP Diliman (UPD) organized the conference “Disaster and Disciplines” on Nov. 18 at the GT-Toyota Asian Center Auditorium.

Phenomenon vs. disaster. “A typhoon is a weather phenomenon, not a disaster,” clarified Dr. Alfredo Mahar Francisco A. Lagmay at the opening program of the conference. Weather disturbances like earthquakes and tsunamis are phenomenon, and will only be considered a disaster “when they cause tragedy to lives and properties,” he continued. A small-scale tragedy is considered an accident while a big-scale tragedy is referred to as a disaster.

Lagmay is a professor at the National Institute of Geological Sciences and current Executive Director of the Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards or Project NOAH of the Department of Science and Technology.

“Due to the recent devastating phenomena, many Filipinos are again thinking of the Big One,” Lagmay said.

In a joint study with the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) looked at 18 earthquake scenarios from 2002 to 2004.

“The Big One.” The scenario from the West Valley Fault, a 100-kilometer fault that runs through six cities in Metro Manila and nearby provinces, is considered the worst-case scenario and is referred as “The Big One.”

According to the Metropolitan Manila Earthquake Impact Reduction Study (MMEIRS) conducted from 2002 to 2004, the Big One will result in the collapse of 170,000 residential houses and the death of 34,000 people. Another 114,000 individuals will be injured while 340,000 houses will be partly damaged in addition to damage to bridges, hospitals, high-rise buildings and other infrastructure.

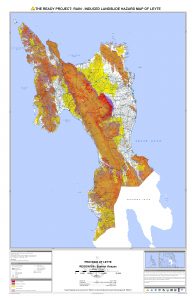

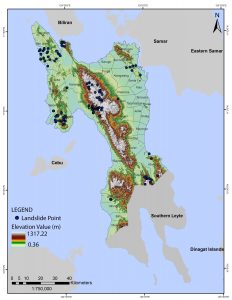

Warnings and maps. Lagmay said the national government should issue reliable, accurate and timely warnings based on weather forecasts both from local and international sources. “One important set of information which should be relayed is on possible hazards and not merely the characteristics of the weather phenomena,” he added.

However, “no amount of accurate warning will work if hazard maps are inappropriate” because evacuation centers can be placed in areas where tragedy is likely to hit.

He believes the use of probabilistic maps over deterministic maps will be more helpful in disaster prevention and development planning because probabilistic maps are “simulated on ground level and look into the likelihood or probability of disasters from the phenomena such as heavy rainfall, storm surge, flooding and landslide.” Deterministic maps, on the other hand, are maps “based on cause and effect analysis and rely solely on past phenomena.”

Probabilistic maps will be helpful “in determining ‘safest places’ for development and evacuation,” Lagmay explained.

One success story in the use of a probabilistic map is the prevention of a possible disaster from the flooding of Tagoloan River in Cagayan de Oro City when typhoon Seniang hit the area on Dec. 28, 2014. “Sensors were placed in the river beforehand due to possible flooding as indicated in the probabilistic map. The sensors registered a water level of up to eight meters. The swelling of the river generated floods that could have turned out into a disaster. Timely warnings in the morning of Dec. 29 were relayed to the communities and by the time floods rushed in at around 3:10 pm, at least 63,000 residents were already out of harm’s way,” Lagmay explained.

An example of a failed disaster prevention, Lagmay said, is the typhoon Yolanda scenario in 2013 where warnings of storm surges were relayed but local government units (LGUs) and residents, who had no experience with storm surges yet, were not able to respond immediately or appropriately.

Engaging all sectors. After typhoon Sendong hit northern Mindanao on Dec. 16, 2011, UP President Alfredo E. Pascual immediately initiated an organized response by sending a disaster response team to Iligan City. Efforts were directed towards Iligan City, instead of also badly-hit Cagayan de Oro City, because the latter was already receiving assistance.

It was the first system-wide effort which was also inter-disciplinary. “The team, composed of medical workers, geologists and engineers, among others, was called the UP Padayon Disaster Response Team,” Dr. Ferdinand C. Llanes, history professor at the UPD College of Social Sciences and Philosophy (CSSP), said. He was director of the Padayon public service office from 2013 to 2014.

To sustain the effort, Llanes initiated a DRRM training course to equip people to respond in times of disaster. Along with this was the preparation of a DRRM handbook, the first draft of which is with the UP Press for review of experts.

Land use plans. The Feb. 19, 2015 issue of the “Business Mirror” reported that “seven out of 10 Filipinos do not go to the public market anymore.” This was validated in “my own field research conducted from August 2014 to December 2015,” Dr. Maria Crisanta Flores, professor at the Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature at the UPD College of Arts and Letters (CAL), said.

Her study, which looks into the urban resiliency of selected emerging urban districts (EUDs), focused on the Binondo District in Manila, Dagupan City in Pangasinan and Iloilo City in Iloilo. EUDs are new spaces of consumption and production slowly replacing traditional marketplaces, downtown areas and commercial centers. These are located in urban centers and have become alternative sites to the old business districts.

In the March 2016 issue of the journal “Landscape and Urban Planning,” Meerow, Newell and Stults defined urban resilience as “the ability of an urban system, and all its constituents, to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change, and to quickly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity.”

Flores said “LGUs, policy makers, investors and developers should review the comprehensive land use plans and comprehensive development plan of the three cities since more lives are at stake in these areas and more structures could be affected. Communities should also be consulted.”

“Binondo, Dagupan and Mandurriao in Iloilo are all vulnerable. Binondo is ‘sinking,’ caused by man-made problems of congestion and reckless construction of high-rise buildings. Dagupan and Mandurriao are ‘shaky’ since these are reclaimed areas from what used to be swamp forests. The July 1990 earthquake and its aftermath should be a reminder to these cities to heed the challenge towards resilient cities,” Flores explained.

The units that organized the conference include the Colleges of Public Administration and Governance, Home Economics, Law, Social Work and Community Development, CSSP, Science, CAL, Engineering with the Archaeological Studies Program and Technology Management Center.